#23. Make-Believe Is How We Find Meaning in Life

Make-believe originates in our playful nature, but it provides the foundation for our serious life purposes.

Dear friends,

This is a relatively short letter, founded on musing not research, extending a bit from my Letter #22 on the playful nature of hunter-gatherer religions. I made the point there that religious stories and beliefs everywhere reflect lessons and ideas crucial to the society in which the devotees live and help give meaning to their lives.

Band hunter-gatherers depended on principles of sharing, cooperation, and equality among themselves and on adapting to the whims of nature for their survival. So, their religions involved multiple deities, none of whom lorded it over the others or over humans, and all of whom behaved rather unpredictably. With agriculture, which involves control of nature, the gods became more controlling and ultimately more threatening and needing of worship and appeasement. As societies became more hierarchical, and social regulation became increasingly centralized, with formal systems of reward and punishment, the pantheon of deities became more hierarchical, eventuating in monotheisms where a single God is ultimate ruler and rewards or punishes people eternally in the afterlife.

The word religion, like so many words, has multiple meanings. We might be better off not using this word for now, and just talking about the beliefs people live by. Some people believe in making money, way beyond what they need for necessities and comfort, and their goal in life is to accumulate as much as they can. Is that a religion? Maybe. It’s a matter of semantics. The primary point I want to make here is that even those of us who claim not to be religious hold beliefs that are matters of faith not objective fact, that give purpose to our lives and help to guide it. Purpose comes from make believe, the beliefs we choose or create for ourselves

What Is the Meaning of Life?

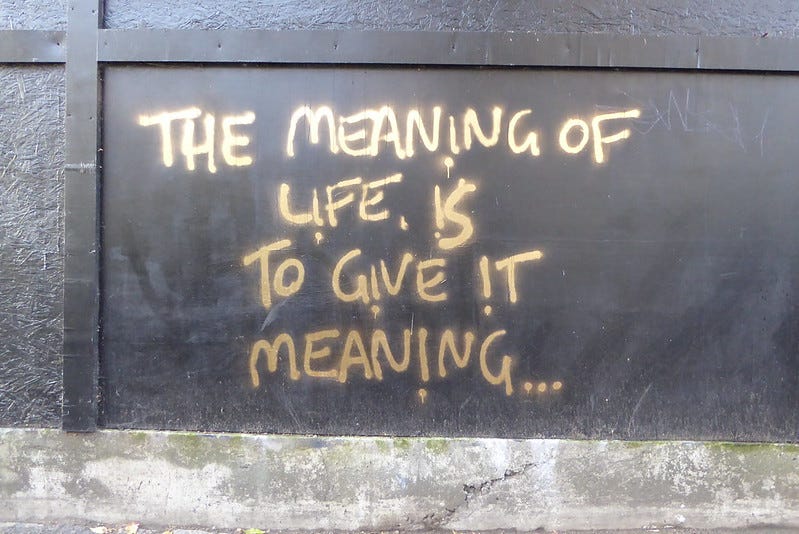

If we were to be totally objective about it (assuming that were possible), we would have to conclude that life has no meaning. Life just is. There are viruses, bacteria, plants, and lots of species of animals, humans among them, and the universe cares about none of them. We humans, perhaps as a side effect of our linguistic and cognitive capacities, want to attribute some purpose to our existence. Life seems empty to us without it. So, we imagine a purpose and a story to support it. We don’t each create these imaginations ourselves, out of nothing. Societies, over generations, have created purposes and stories, some called religions and some not, and we adopt (or inherit) what is most prominent in our corner of the social world or create for ourselves some variant of it.

Some of us, who might call ourselves atheists or agnostics, or “not religious,” might think we are guided by objective, scientific, empirical truths—the kinds of truths that are available to anyone who looks honestly and rationally with the right tools and an open mind. But we delude ourselves. Science can help us solve problems, but it cannot tell us why we care about those problems. Why we care is a matter of faith. Human values are products of imagination, which itself is an ingredient of and derivative of play. Values don’t exist as actual ‘things” out there to be discovered with microscopes, telescopes, or energy-detecting machinery. They are figments of imagination. But what crucial figments they are! They are guides to life; they give us meaning. They are a foundation for joy and for our ability to endure hardship. Sometimes they even lead us to choose hardship.

Unalienable Rights?

Maybe you are a person who cares about human rights. Maybe you, as do I, find meaning, inspiration, and guidance in this famous declaration:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men (i.e., people) are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Let’s play with this a bit. A moment’s reflection will convince us that these truths are not at all self-evident. If they were self-evident there would have been no need to declare them and no need for a revolution. For centuries hardly anyone in Europe would have thought people had such rights. Maybe kings had them, but others? This is a declaration, not a discovery; it is make-believe. “Let’s declare, for the game of life—because we think it will make for a better game (or maybe just cynically to get people on our side)—that these are self-evident truths, not to be challenged.” These are foundation truths for a new game. None of the signers of the declaration (certainly not the slave owners) was living by these truths or fully believed in them, but the declaration set a new course, a long struggle that is still going on.

If we removed “by their Creator” from the declaration, we might create the appearance of removing the faith aspect, but that is an illusion No matter how you believe human beings arrived on earth there is no objective reason to believe in these truths. The belief is faith, make-believe. Yet, for me and for many others, it would be hard to imagine life without holding these truths. These truths have been guiding me in my own life attempt to help bring these “unalienable rights” to children, not just to adults; and many others have struggled mightily to bring them to women and to people whose skin is not white. Imagine the world without such make-beliefs.

There is, I think, a sort of back-and-forth interaction between societal beliefs and the realities of living in any given society. The beliefs reflect the social structure, but variations in the beliefs—mutations if you will—can in turn affect the social structure. Declarations that denied the divine right of kings and claimed that common people have rights led to a history of social changes.

Example of Make Believe in My Unitarian/Universalist Faith

I happen to be a member of a Unitarian/Universalist (UU) church. Unitarianism and Universalism (now combined) are historically branches of Christianity, and because of history the liturgy (at least in the church I attend) has many of the traditional words and symbols of Christianity. There is always a Bible reading, but it is a selected one that can be interpreted to fit the humanistic bent of essentially all our members. The Lord’s Prayer is repeated every Sunday, but I think most of the congregation either grimaces at or completely ignores the “Our Father,” “heaven,” and “Kingdom” part of it, seeing these as historical relics from medieval times, and focuses on “avoiding evil” (however we interpret it) and “forgiving trespasses,” which fit our shared values.

The real beliefs that unite the congregation are found in the UU statement of Seven Principles. We believe in:

• The inherent worth and dignity of every person;

• Justice, equity and compassion in human relations;

• Acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations;

• A free and responsible search for truth and meaning;

• The right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large;

• The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all;

• Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

As a faith community, we don’t try to analyze these beliefs philosophically. We don’t debate as philosophers might about what the words really mean and whether the principles represent natural law, or God’s decree, or make-believe. We just try to live by them in accordance with the broad and general meaning that most people would take from them and from the more specific meanings that each of us might individually ascribe to them. In church I am not a professor; I am a believer. (Well, for the most part I am. My wife might say I grumble sometimes.) The minister and congregation help to reinforce my commitment to a set of guidelines for the game of life that gives purpose to my existence.

Final Thoughts

I’ve given, as examples, humanistic beliefs as make-beliefs that can give meaning to life. But, of course, these are not the only ones. As I said, some find meaning in money. That’s faith, too. Once you are making much beyond what you need for necessities and comfort, there is no objective value in more. Making money becomes an end it itself and in that regard it meets the definition of play. There are people who expend great energy to accumulating as much money and material goods as possible. What can that be but a game? “How much can I make” is not, in principle, different from “how fast can I run” or “how many people can I help.” We are all playing games and those games give us meaning.

Some of you may say that in this letter I’ve strayed beyond my realm of expertise, and you are right. These are musings, so take them for what they are. If they provoke your own musings, then they have served their purpose. If not, then give me another shot.

In my next post I’ll get back on track, with a letter about how hunter-gatherers arranged their work life—their economic existence—in such a way that their work, even though necessary for survival, was highly playful.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions in the comments section below. They will add to the value of this letter and may well contribute to a future letter. If you aren’t already subscribed to this Substack, please do so now, and let others who might be interested know about it. By subscribing, you will receive an email notification of each new letter.

With respect and best wishes,

Peter

"Make believe" is powerful in a context that demands it.

The problem is when make believe starts encroaching into areas of objective truth. Then, rather than briging clarity, it brings confusion. The role of adults is to channel make believe into those areas that benefit from it and restrain it from entering those areas where it only serves to obscure objective truth.

This is the crisis we find ourselves in.

Thank you!

"Science can help us solve problems, but it cannot tell us why we care about those problems."

I do not fully understand where you are coming from with that statement. Evolutionary biology/psychology posits many plausible answers to why we care about many of the things that are most precious to us - our friends, family, spouses, children, sex, food, work, play.

Or am I missing your point? Can you elaborate?