#9. Why Adult-Directed Sports Are No Substitute for Kid-Directed Play

Children learn valuable life lessons in their own games that they don’t learn when adults are in control.

When I was a child, decades ago, you could walk through almost any neighborhood, if it was daytime and school wasn’t in session, and see children playing, no adults around. Now if you walk through those same neighborhoods—even ones that are as safe or safer than ever—you usually see no kids outdoors. Or, if you see any, they are likely wearing uniforms and following the instructions of an adult coach. Worse yet, their parents are likely to be there, watching and cheering them on (and maybe harassing the umpire or referee).

Adult-directed sports are not play and not a substitute for play. In Letter #2 I pointed out that the first two and most essential defining characteristics of play are that it is an activity that is (1) initiated and directed by the players themselves (not by an outside authority) and (2) intrinsically motivated (done for its own sake, not for some reward outside of itself). Adult-directed sports always, obviously, run counter to the first characteristic and usually run counter to the second, because championships, trophies, and judgments from coaches and parents become extrinsic motivators that undermine intrinsic motivation.

Example of Kid-Organized Baseball Compared to Little League Baseball

To illustrate the difference between play and adult-directed sports I’ll contrast here the way kids used to play baseball, when they really played baseball, with what happens in Little League today. I’m using baseball as the example because I played lots of kid-organized baseball and then varsity baseball in high school, so I’m familiar with baseball both as play and as a formal sport. But I could make the same points by contrasting any example of children’s social play with any example of an adult-directed sport.

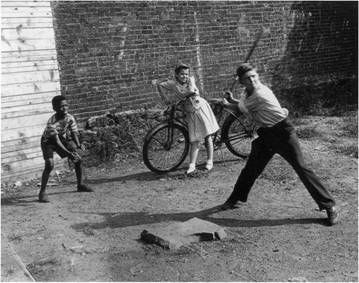

Here’s the kid-organized game as I and millions of others experienced it back when kids were allowed to run free outdoors. A bunch of kids of various ages show up at the vacant lot, hoping they’ll find others to play with. They've come on foot or more often by bicycle, some singly, some with friends. Someone brought a bat, someone brought a ball (which may or may not be an actual baseball), and several brought a fielder's glove. Nobody brought a parent. [I’m cringing now thinking of the embarrassment a kid would’ve felt if his parent showed up to cheer him on.] If there’s not enough to make teams, they’ll play any of several baseball-like games they’ve invented, which can be carried out with as few as three players. If at least 8 show up--enough to have a pitcher, catcher, and a couple of fielders on each team—then, yay, a “real” game of baseball. The two reputably best players serve as captains, and they choose up sides. They lay out the bases--which might be hats, bits of trash found in the lot, or any other objects of suitable size. With small team sizes, they might move first and third bases inward to reduce the fair ball area that the fielders must cover. And then everyone gets involved in a discussion about the rules for that day’s game. Nothing is standard and there’s no adult authority telling them what to do, so everything must be improvised.

Now, here’s the Little League game as it’s commonly played today. It's played on a manicured field, which looks like a smaller version of the fields where professional games are played. Most kids are driven there, partly because parents think it would be unsafe for them to go themselves and partly because parents are behind this activity. Many parents stay for the game, to show their support for their young players. The teams are predetermined; they are part of an ongoing league. Each team has an adult coach, and an adult umpire is present to call balls, strikes, and outs. An official score is kept, and, over the course of the season wins and losses are tracked to determine the championship team. Some of the players are there because they really want to be there; others are there because their parents believe this is good for them and have coaxed or pushed them into it.

Lessons Learned in the Informal (Kid-Organized) Game that Are Not Learned in the Formal Game

The informal, self-directed way of playing baseball or any other game contains valuable lessons that do not lie in the formal, adult-directed game. Here are five that are among the most valuable lessons that anyone can learn in life.

Lesson 1: To keep the game going, you must keep everyone happy, including the players on the other team.

The most fundamental freedom in all true play is the freedom to quit. That’s what keeps the activity in the realm of play. In the informal game, nobody is forced or pressured to be there. There are no coaches, parents, or other adults who will scold or be disappointed if someone quits. The game can continue only as long as enough choose to continue. Therefore, if you want to keep the game going, you must do your share to keep the other players happy, even those on the other team.

This means you show certain restraints in the informal game, which go beyond those dictated by the stated rules and derive from your understanding of each player’s needs and desires. You don't run full force into second base, bowling the second baseman over, if he is smaller than you and could get hurt, even though in the formal game that might be considered good strategy and a coach might scold you for not running as hard as possible. This attitude, in fact, is why children are injured less frequently in informal sports than in formal sports, despite parents' beliefs that adult-directed sports are safer. If you are pitching, you pitch softly to little Timmy, because you know he can't hit your fastball. Even your own teammates would accuse you of being mean if you threw your fastest pitches to Timmy. But when big, experienced Marvin is up, you throw your best stuff, not just because you want to get him out but also because anything less would be insulting to him. The golden rule of social play is not, Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Rather, it is, Do unto others as they would have you do unto them. The equality of play is not the equality of sameness, but the equality that comes from granting equal validity to the unique needs and wishes of every player.

To be a good player of informal sports you can’t just blindly follow rules. Rather, you must hone your skills as a psychologist, to see from others’ perspectives, to understand what others want and provide at least some of that for them. If you fail at that, the others will leave, and you will be left alone. In the informal game, keeping your playmates happy is far more important than winning; and that’s true in life as well. For some children this is a hard lesson to learn, but the drive to play with others is so strong that most eventually do learn it if allowed plenty of opportunity to play—plenty of opportunity to fail, suffer the consequences, and then try again.

Lesson 2: Rules are modifiable and are generated by the players themselves.

Because nothing is standardized in the informal game, the players must make up and modify rules to adapt to varying conditions. If the vacant lot is small and the only ball available is a rubber one that carries too well, the players may decide that any ball hit beyond the lot’s boundary is an automatic out. This causes the players to concentrate on placing their hits, rather than smashing them. Alternatively, certain players--the strongest hitters--may be required to bat one-handed, with their non-dominant hand, or even (as I recall in one game) to bat with a broomstick. As the game continues and conditions change, the rules may change further. None of this happens in Little League, where the official rules are inviolable and interpreted by an adult authority rather than by the players. In the formal game, the conditions must fit the rules rather than the other way around.

The famous developmental psychologist Jean Piaget noted long ago, in a classic study of children playing marbles, that children acquire a higher understanding of rules when they play just with other children than when they are directed by adults. Adult direction leads to the assumption that rules are determined by an outside authority and are not to be questioned. When children play just among themselves, however, with no official authority present, they come to realize that rules are just conventions, established to make the game more fun and more fair, and can be changed to meet changing conditions. For life in a democracy, few lessons are more valuable than that.

Lesson 3: Conflicts are settled by argument, negotiation, and compromise.

In the informal game, with no umpire, the players must not only make and modify the rules, but must decide all along the way whether a hit is fair or foul, whether a runner is safe or out, whether the pitcher is or isn't being too mean to little Timmy, and whether or not Marvin should be allowed to hog his brand new glove rather than share it with someone on the opposing team who doesn't have a glove. Some of the better or more popular players may have more pull in these arguments than others, but everyone has a say. Everyone who has an opinion defends it, with as much logic as he or she can muster; and ultimately consensus is reached.

Consensus doesn't necessarily mean complete agreement. It just means that everyone consents; they're willing to go along with it for the sake of keeping the game going. Consensus is crucial if you want the game to continue. The need for consensus in informal play doesn't come from some highfalutin moral philosophy; it comes from practical reality. If a decision makes some people unhappy some of them may quit, and if too many quit the game is over. So, you learn, in the informal game, that you must compromise if you want to keep playing. Because you don't have a king who decides things for you, you must learn how to govern yourselves.

Once I was watching some kids play an informal game of basketball. They were spending more time deciding on the rules and arguing about whether certain plays were fair or not than they were playing the game. I overheard an adult nearby say, "Too bad they don't have a referee to decide these things, so they wouldn't have to spend so much time debating." Well, is it too bad? In the long run of their lives, which will be the more important skill--shooting baskets or debating effectively and learning how to compromise? Kids playing sports informally are practicing many things at once, and the least important of those may be the sport itself.

Lesson 4: There is no real difference between your team and the opposing team.

In the informal game, the players can see at every moment that their division into two teams is arbitrary and serves purely the purpose of the game. New teams are chosen at every game. Billy may have been on the "enemy” team yesterday, but today he is on your team. In fact, teams may even change composition as the game goes along. Billy may start off on the enemy team, but then move over to your team to make the sides even when two of your teammates go home for supper. Or, if both teams are short of players, Billy may catch for both. Clearly, the concept of "enemy" or "opponent" in informal sports is one that has to do with fantasy and play, not reality. It is temporary and limited to the game itself. Billy is just pretending to be your opponent when he is on the other side; he isn't in reality. In that sense the informal game is like a pure fantasy game in which Billy pretends to be an evil giant trying to catch you and eat you.

In contrast, in formal league sports, teams remain relatively fixed over a whole series of games, and the scores, to some degree, have real-world consequences--such as trophies or praise from adults. The result is development of a long-lasting sense of team identity and, with it, a sense that "my team is better than other teams"--better even in ways that have nothing to do with the game and may extend to situations outside of the game. A major theme of much research in social psychology and political science concerns ingroup-outgroup conflict. Cliques, gangs, ethnic chauvinism, nationalism, wars--these can all be discussed in terms of our tendency to value people we see as part of our group and devalue those we see as part of another group. Formal team sports feed into our impulse to make such group distinctions, in ways that informal sports do not. Of course, enlightened coaches of formal sports may lecture about good sportsmanship and valuing the other team, but we all know how much good lecturing does for children--or for adults, for that matter.

Lesson 5: Playing well and having fun really ARE more important than winning.

"Playing well and having fun are more important than winning," is a line often used by Little League coaches after a loss, rarely after a win. But with spectators watching, with a trophy on the line, and with so much attention to the score one wonders how many of the players believe that line, and how many secretly think that Vince Lombardi had is right. The view that "winning is everything" becomes even more prominent in formal sports as one moves up to high school and then to college sports, especially in football and basketball, which are the sports that American schools care most about. Eventually, as they ascend the ladder, only a small minority make the teams. The rest become spectators for the rest of their lives and grow fat in the stands and on the couch unless they learn to play informally.

In informal sports playing well and having fun really are more important than winning. Everyone knows that; you don't have to try to convince anyone with a lecture. And you can play regardless of your level of skill. The whole point of the informal game is to have fun and stretch your own skills. You may stretch your skills in new and creative ways, which would be disallowed or jeered at in the formal game. You might, for example, try batting with a narrow stick, to improve your eye. You might turn easy catches in the outfield into difficult over-the-shoulder catches. If you are a better player than the others, these are ways to self-handicap, which make the game more interesting not just for yourself but also for others. In the formal game, where winning matters, you could never do such things; you would be accused of betraying your team. Of course, you must be careful about when and where to make these creative changes in your play, even in the informal game. You must know how to do it without offending others or coming across as an arrogant show-off. Always, in informal play, you must be a psychologist.

In my experience, both as a player and observer, players in informal sports are much more intent on playing beautifully than on winning. Beauty may involve new, creative ways of moving that allow you to express yourself and stretch your physical abilities while still coordinating your actions to mesh with those of others. The informal game, at its best, is an innovative group dance, in which the players create their own moves, within the boundaries of the agreed-upon rules, while taking care not to step on each other’s toes. I’ve played formal sports, too, where varsity championships were at stake, and those games were not creative dances. If stepping on toes helps you win those games, you step on them.

------

Life is an Informal Game

Which is better training for real life, the informal game or the formal one? The answer seems clear to me. Real life is like an informal game. I’m tempted even to say that real life is an informal game. The rules are endlessly modifiable, and you must do your share to create them. There are in the end no winners or losers; we all wind up in the same place. Getting along with others is far more important than beating them. What matters in the end is how you play the game, how much fun you have along the way, and how much joy you give to others. These are the lessons of informal social play, and they are far, far more important than learning the coach’s method for throwing a curve ball or sliding into second base. I’m not against formal sports for kids who really want them, but such sports are no substitute for informal play when it comes to learning the lessons that we all must learn for a satisfying life.

Notes

Some of you, reading this and remembering your experiences with kid-directed play, may say that I am idealizing here. I’m describing kids’ play at its best. Yes, that’s true. There indeed were bullies. There were times when we got mad. Not everyone was treated fairly and kindly. But that’s life, too, and learning to deal with meanness and anger in play is training for dealing with them later in life, when the stakes are higher. I’ve been thinking about a future letter titled something like, “we must trust kids to behave not just well but also badly.”

Some of you quite likely have stories to tell about your childhood play that may in some ways conform with and in other ways run counter to what I have written here. Your story, in the comments section here, would add to the interest of this letter. I invite you to share it.

If you like this this series of letters, please subscribe if you haven’t already, and please let others know about it.

This is all true, but what is interesting is that I find that my kids get more unsupervised/loosely supervised free play at their siblings' Little League games than almost anywhere else. They don't get it as much in neighborhoods anymore, but at games, much like in the neighborhoods of old, it's not so much that no parents are watching as that they all are - a little. Groups of mixed-age kids making up their own fun on the sidelines, under bleachers, on unused fields. Rolling down hills, scaling fences to get into places they weren't supposed to be, but not like REALLY REALLY not supposed to be. I brought books to keep my youngest occupied - could I ever have guessed that he and his friend would have invented the game of "book hiding" and played it every week, or that if they did choose to read, I wouldn't have to read to my non-reader? An older friend read for him, or they sounded out words together, which would have required pulling teeth at home during homework time. At 5, spending the better part of a 2-hr game out of my sight because home base is a certain group of rocks or under a given tree, but also because there are other parents around who I trust to intervene if something really goes off the rails. At our Little League fields, the oldest kids even show up - on bikes, sans parents - an hour or more before their games start to hang out, watch the younger kids play, etc. Their parents do come watch games, but those kids have plenty of unsupervised time first.

This is spot on. I would add to informal play some anecdotes from my high school experience. We played pick up basketball all the time. If nothing else was going on...we always had basketball, 3 guys or a dozen. There were 4 courts by the campus that we went to all the time. High school kids to adult men, shooting for teams, playing with/against each other. As a 16 year old, playing adult men and interacting and working out problems with them gave me confidence and improved my game. The interactions though were extremely helpful as a 22 year old in the workplace, interacting with older males. That was the power of sport.