#50. The Origin and Harm of Federal Education Mandates

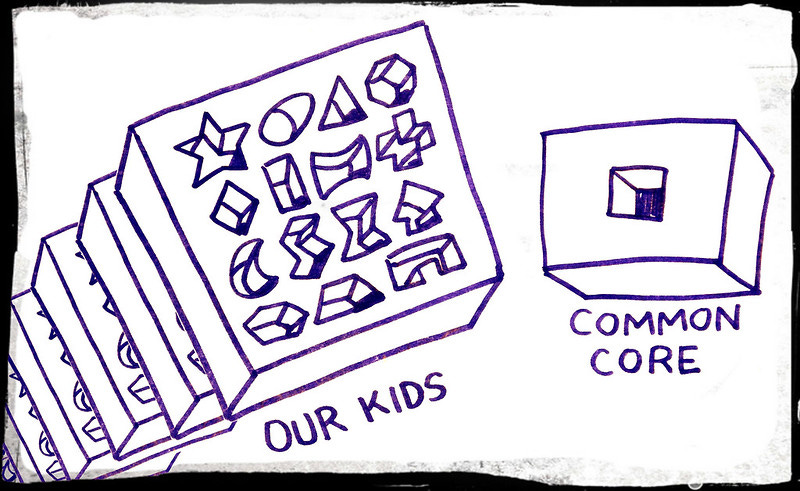

No Child Left Behind Act by Common Core made U.S. schools far less pleasant for all.

Dear friends,

Adelle (a person I know well whose name I have changed here) used to love teaching. She didn’t share my strong dislike of our traditional system of compulsory schooling. She taught various 6th grade subjects over a 22-year period in a large public middle school. She loved the kids, and the kids loved her. Then, in 2012, well before eligibility for a full pension, she resigned.

In a recent conversation, she explained why. Up until a year or so before 2012, she had felt free to teach in ways that seemed to work, ways that were responsive to the varying needs and interests of her students and that the students seemed to enjoy. She could be creative. She could engage in conversations with the students and respect their thoughts. She could promote critical thinking. Then things changed. Administrators began to take her and other teachers’ freedoms away. They wanted every section of any given class to be on the same predetermined page every day. Teachers who strayed—who might wander off with their class in a direction not on the prescribed agenda—were reprimanded. She was being reprimanded by an administrator younger, less experienced, and—this is my word not hers—stupider than her. The state in which she was teaching had not yet officially implemented Common Core, but had adopted it and schools were gearing up to implement it.

Teaching this way saddened Adelle, as it saddened her students. She became depressed and took a leave of absence. After the leave, she said, “I can’t return.” In my recent conversation with her she told me she was glad she quit when she did, because her friends who continued to teach told her that things only got worse in subsequent years. And I know from other sources that, beginning around 2010, changes like this were occurring in many schools throughout the nation. These were the somewhat delayed effects of the No Child Left Behind Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2001.

Our High School Debate Question in 1962

Step back in time. In 1962 I was a senior at tiny Cabot High School, in Cabot, Vermont. There were 13 kids in my graduating class. Despite our tiny size, we had a school debate team that participated in regional and state tournaments with schools of all sizes. The state-wide debate question that year was this: “Should the Federal Government provide financial aid to public schools?”

Every team had to argue both sides of the question. The way it worked was that each team included two members who argued the affirmative and two who argued the negative. So, in any given match with another team, our affirmative pair debated their negative pair, and our negative pair debated their affirmative pair.

I was a member of our affirmative side, arguing “yes” to the question of Federal aid to education. My partner and I won almost every debate we were in. But any pride I might have in that was countered by my knowledge that the affirmative pairs on almost all the teams in the state won all or nearly all their debates.

It was easy to make the affirmative case. All you had to do was point to statistics showing that schools in poor states, like Mississippi, were spending much less money on education than were schools in rich states, like Massachusetts, and make the case that less money means poorer education. I also recognized, even then, that the affirmative case was abetted by the fact that the judges in these debates were almost always school administrators or teachers who would dearly love to get some of that federal money. We in the affirmative played to their wishes.

I said that my partner and I won “almost” every debate. We lost one. The star of the pair that beat us was probably the most brilliant debater in the state. I’m not just saying that because she beat us so soundly. I learned later that she won every debate she was in throughout her high school career.

Her basic argument was this: “He who pays the piper calls the tune.” With federal money, she argued, will come federal control. Local school boards, school principals, and teachers—the people on the ground, who know the kids, who can see what works and what doesn’t—will lose control of the curriculum and how it is taught. Education decisions will be made by politicians and bureaucrats who have no direct knowledge of how kids learn and will look only at numbers, not at kids.

She had found a way to appeal to the principals and teachers judging the debates that was even more powerful than prospects of higher salaries and nicer school buildings. Other debaters for the negative also used the argument that federal aid would mean federal control, but they were far less effective in spelling out why such control would be harmful, how it would affect people like the students, teachers, and principals sitting there in the room listening to her. I see now that her words were not just effective in winning debates; they were prophetic.

A Bit of History Behind Common Core

In 1983, a commission created by President Ronald Regan, issued its report in the form of a book with the scary title, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Education Reform. The commission consisted of 18 people, selected by Secretary of Education Terrel Bell, most of whom had already complained that American schools had become too lax. Of the 18 selected, only one was a teacher and none were academics specializing in education. They were hand-picked to come to a predetermined conclusion.

The report, authored primarily be James Harvey, proclaimed, “The educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a People... If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war." The report went on with a long list of recommendations including those for standardizing the school curriculum, increasing the length of the school day and year, and creating more rigorous means of evaluating the performances of students, teachers, and whole schools. The report set a new tone to discussions of education in America and countered a 1970s trend toward progressive views that emphasized the value of student happiness, choice, and individual differences in interests and learning styles.

A Nation at Risk set the stage, ultimately, for federal interventions in America’s schools. The most significant of these was the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), passed by Congress and signed by President George W. Bush in 2001. This new law did not set academic standards but instead required states to set them and prove that students were scoring higher from year to year relative to those standards. The inducement for compliance, of course, was money. To receive federal school funding and continue receiving it, states had to assess student performance regularly with standardized statewide exams and show that scores were improving from year to year. To comply, states developed ways of holding teachers and schools accountable, and those ways were generally based entirely on students’ scores on the state exams. The era of teaching to the test began.

The mandate established by NCLB was somewhat modified during the Obama administration, with passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015. Of course, the title of this act, like that of the previous one, is just wishful or delusional thinking or, more cynically, deceptive advertising. There is no imaginable way to legislate academic success. There is no conceivable program that can force every student to “succeed” or not “fall behind” whatever arbitrary standards some commission decides upon. But that’s another story. The ESSA somewhat modified the requirements for federal money set by NCLB, giving a little more power to the states to determine the criteria they would use to measure school success or failure, but there was no fundamental change.

As they struggled to meet the federal requirements most states chose to work together—through an initiative sponsored by the National Governor’s Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers—to create a common set of standards. The result is what came to be called the Common Core Standards. Most states adopted the standards immediately when they were released, in 2010. A few adopted them a year or more later, and a few of the initial adopting states dropped them. Now, in 2024, 42 states are legally tied to Common Core and the remaining states have created their own means of meeting the federal requirements for funding, which are generally not much different from Common Core.

Effects of Common Core: Prelude to My Next Letter

Twelve to fourteen years have passed since Common Core or something like it has been adopted by the states. What have been the effects? I’ll save a discussion of that for my next letter, but here’s a preview.

The education gap between rich and poor has increased, not decreased. Test scores have gone up, but that seems to be more a result of gaming the system than meaningful learning. What used to be fun in schools—including recesses, lunch periods long enough for socializing, art and music classes, and creative writing assignments just for fun—have been dropped or largely curtailed, all for the sake of more drill in the very narrow range of subjects relevant to the state tests. Anxiety has increased among everyone involved with the schools, especially teachers and students. Teachers in many schools feel disempowered and in fact are disempowered. Many of the best teachers have quit.

That young woman who slayed me in that 1962 debate had it right. Once federal money was on the table, schools sacrificed their souls to get it. They also sacrificed, as it turns out—though I don’t think my debate opponent specifically predicted this—the mental health of their students. More on that in the next letter.

Further Thoughts

This Substack series is, in part, a forum for thoughtful discussion. I greatly value readers’ contributions, even when they disagree with me, and sometimes especially when they do. You will notice in reading comments on previous letters that everyone is polite. Your questions and thoughts will contribute to the value of this letter for me and other readers. If you have witnessed effects of NCLB or Common Core, good or bad, or relevant questions, I and others would like to hear about them.

If you aren’t already subscribed to Play Makes Us Human, please subscribe now, and let others who might be interested know about it. By subscribing, you will receive an email notification of each new letter. If you are currently a free subscriber, consider converting to a paid subscription. I use all funds that come to me from paid subscriptions to help support nonprofit organizations aimed at bringing more play and freedom to children’s lives.

With respect and best wishes,

Peter

Federal funds to public schools represents a small percentage of monies spent; yet the requirements to comply with them take up a substantial bandwidth of resources. It is hard to believe the benefits outweigh the costs from either a quantitative or qualitative perspective. I would love to see an analysis at the district and state levels.

Here’s another prophet on academic freedom: Martin Luther King Jr.

“My days in college were very exciting ones. There was a free atmosphere at Morehouse, and it was there I had my first frank discussion on race. The professors were not caught up in the clutches of state funds and could teach what they wanted with academic freedom. They encouraged us in a positive quest for a solution to racial ills. I realized that nobody there was afraid. Important people came in to discuss the race problem rationally with us.“

https://scottgibb.substack.com/p/mlk-jr-on-academic-freedom