#65. The False Analogy Between Problematic Internet Use and Drug Addiction

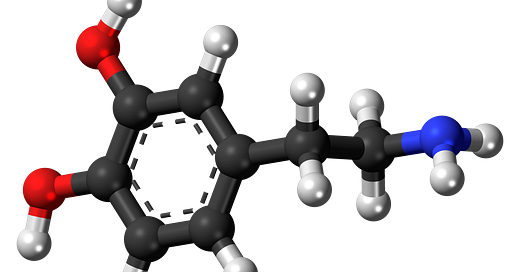

Fear is created by false comparisons of a brain on video games to a brain on drugs.

Dear Friends,

In Letter #64 I briefly described six reasons why the terms “addiction” and “disorder” are harmful in understanding and treating problematic internet use. I listed these as (1) false analogy to substance addictions; (2) disempowering the person who has the problem; (3) stereotyping the person who has the problem; (4) implying that the behavior is causing the problem when it may be a consequence of the problem; (5) demonizing the activity and promoting bans, especially for kids; and 6) the problem of diagnosis. In this letter, partly in response to comments and questions on Letter #64, I will elaborate on the first item on this list.

Striking Fear in the Hearts of Parents

“IT’S ‘DIGITAL HEROIN’: HOW SCREENS TURN KIDS INTO PSYCHOTIC JUNKIES.”

This was the headline of an article in the New York Post (August 27, 2016) by psychiatrist Dr. Nicholas Kardaras. The article was sent to me by several worried parents soon after it was published. It comes across as a dire warning to parents about the dangers, for kids, of all sorts of activities involving “screens,” but especially video games.

The article began with a possibly apocryphal story of a mother who, against her better judgment, bought her young son an iPad and allowed him to play the popular game Minecraft (a nonviolent building game, attractive to kids and adults of all ages). The story went on to say that, one evening when the mother went into the boy’s bedroom, …“She found him sitting up in his bed staring wide-eyed, his bloodshot eyes looking into the distance as his glowing iPad lay next to him. He seemed to be in a trance. Beside herself with panic, Susan had to shake the boy repeatedly to snap him out of it. Distraught, she could not understand how her once-healthy and happy little boy had become so addicted to the game that he wound up in a catatonic stupor.”

Yikes.

The article continued: “We now know that those iPads, smartphones and Xboxes are a form of digital drug. Recent brain imaging research is showing that they affect the brain’s frontal cortex — which controls executive functioning, including impulse control — in exactly the same way that cocaine does.” Although Kardaras attributed these horrendous effects to all sorts of screen use, he particularly singled out video gaming, when he wrote: “That’s right—your kid’s brain on Minecraft looks like a brain on drugs.”

Kardaras’s article is the most outlandish of the scare articles I’ve seen, but it is far from the only one I’ve seen, both before and after this one was published. The impression I get from parents’ reactions is that the scariest articles are those that say or imply that video gaming, or using social media, affects the brain in the same way that addictive drugs do.

The Misleading Dopamine Theory of Addiction

The patina of science behind the original claims that video gaming is like taking an addictive drug derives largely from a 1998 research study in which eight adult men were hooked into a PET (positron emission tomography) brain scanner and then spent 50 minutes playing a video game and another 50 minutes doing nothing (Koepp et al, 1998). By using a radioactive tracer, the researchers were able to estimate the amount of the neurotransmitter dopamine that was released in a particular brain area, the striatum, under both conditions. They found that about twice as much dopamine was released during game play as during the period when the participants were just looking at a blank screen.

The article describing the study makes it clear that the research had nothing to do with addiction and was not even fundamentally about video gaming. Previous research with laboratory animals had shown that dopamine is released in the striatum whenever an animal is involved in any motivated task, such as pressing a lever for a food reward. The purpose of the PET study was to see if the same happened in humans. The video game—a simple one involving manipulating a digital tank through a series of barriers—was used because it was something the participants could do while hooked up to the PET scanner. To assure that this was a motivated task, somewhat comparable to the tasks used with animals, the researchers told the participants they would get a monetary reward for success at getting the tank through the barriers. The study confirmed what was already known from animal research and added support to the theory that striatal dopamine is involved in goal-directed behaviors in humans as well as in other animals.

An unfortunate consequence of the study is that some people (who, I suspect, did not read the study but only heard reports of it) seized upon the facts that the researchers happened to use a video game as the task and that addictive drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and amphetamine also cause release of dopamine in the striatum, and then used those facts to bolster their claim that video games cause addiction. Of course, if striatal release of dopamine at the level these researchers found truly caused addiction, then any goal-directed activity would cause addiction.

Nobody knows for sure that dopamine release is a crucial aspect of the addictiveness even for the drugs just mentioned, as there are mixed findings on this. But, as many researchers have pointed out, the amount of dopamine released in response to those drugs is estimated, from animal studies, to be much higher and more prolonged than the amount released in this study with a video game (Etchells, 2024).

This story illustrates a more general point about moral panics. During such a panic, crusaders often take any scientific findings that might be construed, out of context, as evidence for their belief and blow it up beyond reason. When the blown-up story is repeated enough, even some scientists, who don’t bother to go back and read the original articles, begin to believe the fear mongers’ story.

I should add, as a bit of a digression, that research, over the past 15 years or so has greatly altered the original story about the role of dopamine in rewarded behaviors. In the popular press we still see phrases like “dopamine rush” to refer to any rewarding experience (e.g. here), or see dopamine described as “the pleasure transmitter.” But, in fact, research shows that dopamine is involved in many pathways in the brain, serving many functions, and is not essential for the experience of pleasure. I confess that in one of my Psychology Today blog posts years ago, I too made the error of stating that dopamine transmission underlies the experience of pleasure.

Multiple research studies have shown that blocking dopamine transmission with a drug does not reduce the sense of pleasure in humans and also doesn’t do so in laboratory animals (as assessed through their facial expressions). Research shows repeatedly that blocking dopamine reduces the drive to seek rewards, especially if much effort is involved, but does not reduce the pleasurable effect of a reward. Stated differently, anything you do that involves considerable effort and attention is promoted by neural systems in your brain that involve dopamine. If you are interested in such research, a recent comprehensive review of it can be found here.

What Effects Does Video Gaming Have on the Brain?

Around the same time that Kardaras’s scare article was published, neuroscientist Marc Palaus and his colleagues (2017) published a systematic review of all the research they could find—derived from a total of 116 published articles—concerning effects of video gaming on the brain as assessed by brain scans using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The results are what anyone familiar with brain research would expect. Games that involve visual acuity and attention activate parts of the brain that underlie visual acuity and attention. Games that involve spatial memory activate parts of the brain involved in spatial memory, games that involve decision making activate parts of the brain involved in making decisions. And so on.

In fact, some of the research reviewed by Palaus and his colleagues, as well as more recent research, indicates that gaming not only results in transient activity in many brain areas, but, over time, can cause long-term growth and increased effectiveness of at least some of those areas. Extensive gaming may increase the volume of the right hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex, which are involved in spatial memory and navigation. It may also increase the volume of prefrontal regions the brain that are involved in executive functioning, including the ability to solve problems and make reasoned decisions.

Such findings are consistent with multiple studies showing that video gaming improves basic perceptual and cognitive abilities (see my summary here and a more recent published review here). Your brain is, in this sense, like your muscular system. If you exercise certain parts of it, those parts grow bigger and more powerful. Yes, video gaming can alter the brain, but the documented effects are positive, not negative.

Video gaming, like many other mentally challenging activities, is exercise for the brain in the same sense that vigorous outdoor play is exercise for the body.

I have focused here on video gaming, because that is where more research has been conducted, but, in the popular press, you will read claims or hints that dopamine release during social media use underlies “social media addiction.” The false dopamine story continues on. I’ll write more about social media in future letters.

Further Thoughts

Of course, none of what I have said here is meant to imply that video gaming and social media use are always completely beneficial in their effects. It is reasonable to talk about “problematic” gaming or social media use. Let’s just not call it “addiction” and pretend it’s like a drug addiction where physiological dependence and painful withdrawal symptoms occur. I’m OK with calling such problematic behaviors “compulsions,” and in a future letter I may discuss strategies for dealing with compulsions.

Please feel free to comment, below. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are valued and treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Readers’ comments add to the value of these letters for everyone.

If you aren’t already subscribed to Play Makes Us Human, please subscribe now, and let others who might be interested know about it. By subscribing, you will receive an email notification of each new letter. If you are currently a free subscriber, consider converting to a paid subscription for just $50 for a year (or, better yet, a “founding subscription” for $100). I use all funds that come to me from paid subscriptions to help support nonprofit organizations aimed at bringing more play and freedom to children’s lives.

Note Concerning Periodic Live Online Meetings for Paid Subscribers

I described the plan for online meetings in my previous (unnumbered) letter here. In response to that, and to the letter before that, two or three readers said they would love to join such meetings but truly can’t afford the $50 paid membership fee. At least one or two generous readers said they would be willing to gift a subscription to someone who is strongly motivated to attend the online meetings but can’t afford a subscription.

So here is what I have done. I have created a Google Doc where people who are willing to offer a gift subscription can put their name and email address. By accessing the Google Doc, anyone looking for such a gift can—if a potential giver is listed there—email that person and make their request by private email—no need to make it publicly on the Google Doc or even to say who you are.

Here is the link to the Google Doc: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hfyekoZEOafLhcgnYhgcIglEgZw6fCNfJuwz2stYwJQ/edit?usp=sharing

With respect and best wishes,

Peter

Reference

Etchells, P. (2024). Unlocked: The real science of screen time (and how to spend it better). London: Little Brown.

Koepp, M. J. et al (1998). Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game. Nature, 393, 266-268.

Palaus, M., et al (2017). Neural basis of video gaming: A systematic review. Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, 11, article 248. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00248. eCollection.

I have two teens who have had unfettered access to computer technology most of their lives (I fought it when my elder was little but I healed that fear and need to control in myself and the issue resolved.)

And they have several friends who are from similar situations. Now that some of them are young adults, I can confirm that *the tech is not the problem.* The family and community environment drives so much of the dynamic.

All the effort that was needed was *within me.* Once I did that, it all flowed.

DrK mentioned that any video gamer who is able to beat Dark Souls by definition does not have a problem with motivation. Its only that their motivation doesn't correspond to what you think it should.

I also want to point out that we often use the phrase "the real world" referring to life outside of school. My question is, if the life inside of school is implied to be fake, and correctly so, then why is it so much better than the world of Super Mario??